What about the music?

An inside look with the Virginia Symphony Orchestra

Highlight: Bela Fleck & Gershwin

The Performers

Eric Jacobsen

Conductor

Hailed by the New York Times as “an interpretive dynamo,” conductor and cellist Eric Jacobsen has built a reputation for engaging audiences with innovative and collaborative programming. He is the newly-named Music Director of the Virginia Symphony, becoming the 12th music director in the orchestra’s 100-year history.

Jacobsen is Artistic Director and conductor of The Knights, and serves as the Music Director for the Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra. Jacobsen founded the adventurous orchestra The Knights with his brother, violinist Colin Jacobsen, to foster the intimacy and camaraderie of chamber music on the orchestral stage. Eric splits his time between New York and Orlando with his wife, singer-songwriter Aoife O’Donovan, and their daughter.

Bela Fleck

Banjo

“Béla Fleck has taken banjo playing to some very unlikely places — not just bluegrass and country and “newgrass,” but also into classical concertos, jazz and a documentary about the banjo’s deep African roots, not to mention the time he toured with throat singers from Tuva. He’s also baffled the Grammy awards, winning for country and jazz in the same year and also winning in pop, world music, classical crossover and, yes, folk. That’s a lot of territory for five strings.”

— JON PARELES, THE NEW YORK TIMES

Program notes by —©Jennifer More, 2023

The Creators

Duke Ellington

(1899-1974)

Sophisticated Lady

One of the greatest jazz musicians in American history, Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington was born in Washington, D.C., in 1899. His parents, Daisy and James Ellington, appreciated the finer things in life, and Edward’s “duked up” appearance earned him the nickname “Duke.” In 1917, he formed his first band, “Duke’s Serenaders.” By 1931, he was touring the entire United States and Europe while appearing in movies and recording albums. In 1932, “Sophisticated Lady” appeared in an instrumental version featuring Toby Hardwick on alto sax, Barney Bigard on clarinet, Lawrence Brown on trombone, and Ellington on piano. Upon entering the charts on May 27, 1933, it immediately rose to number 3. Ellington described the words, written by publisher Irving Mills and added after the fact, as “wonderful—but not entirely fitted to my original conception”—three of Ellington’s grade school teachers. “They taught all winter and toured Europe in the summer,” Ellington explained. “To me, that spelled sophistication.”

Lili Boulanger

boo·laan·zhay

(1893-1918)

D’un Matin de printemps

Born on August 21, 1893, Lili Boulanger was surrounded by musicians. Her father Ernest was a composer, her mother Raïssa Mischetzky was a performer, her older sister Nadia mentored many famous composers—including Aaron Copland and Astor Piazzolla—and one of their closest friends was Gabriel Fauré. Unfortunately, as a child, Boulanger was struck with bronchial pneumonia, leaving her with chronic intestinal tuberculosis that eventually led to her death. Far from a victim of circumstance, Boulanger became determined to win the coveted Prix de Rome in composition, studying privately as the result of her condition instead of enrolling full-time at the Paris Conservatoire. At 19, she won on her second try—the first woman to earn the distinction. Five years later, just two months before she succumbed to her terminal illness, Boulanger composed the last works notated in her own hand: D’un Matin de printemps (“Of a Spring Morning”) and its companion, D’un Soir triste (“Of a Sad Evening”). The work’s vigor belies its creator’s fragile health, while Boulanger’s rich exploration of color, melody, and harmony leaves listeners wondering where the composer’s talent might have taken her.

George Gershwin

(1898-1937)

Rhapsody in Blue

(arranged for banjo by Bela Fleck)

Given the esteem in which jazz is held today, it is hard to imagine that in the 1920s, debate raged over its status as music. One of its primary defenders was Paul Whiteman, who played a significant role in making jazz respectable. Whiteman planned a concert in Aeolian Hall on February 12, 1924, entitled “An Experiment in Modern Music,” with a panel of judges—including composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, violinists Jascha Heifetz and Efrem Zimbalist, and singer Alma Gluck—to investigate the question, “What is American music?” Whiteman asked George Gershwin to provide a piece for the event. Gershwin agreed—and forgot all about it until his brother Ira saw an advertisement for the concert in the January 3 edition of the Herald Tribune. Gershwin got to work on January 7, conceptualizing the piece while traveling back and forth to Boston for a show called Sweet Little Devil. As he wrote of the Rhapsody’s genesis,

It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty bang that is often so stimulating to a composer…And there I suddenly heard—and even saw on paper—the complete construction of the rhapsody, from beginning to end. I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America—of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our blues, our metropolitan madness.

Rhapsody in Blue was created as a jazz composition—collaborative and, to a certain extent, improvised (and in this sense, Bela Fleck’s arrangement is particularly appropriate). Whiteman’s clarinetist Ross Gorman, able to play a two-octave upward glissando, inspired the work’s unforgettable opening. As Gershwin described the genesis of the main romantic melody at a party in New York, “I heard myself playing a theme that must have been haunting me inside, seeking outlet. [It] oozed out of my fingers.” Gershwin improvised many of the piano solos in performance, writing the instruction, “Wait for nod,” in the score. And Ira Gershwin suggested the title, “Rhapsody in Blue,” after the number of “blue notes,” or accidentals, in the work.

Cole Porter

(1891-1964)

Within the Quota

Born in Indiana in 1891, Cole Porter composed some of the most famous entries in the American songbook, including “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” “My Heart Belongs to Daddy,” “Begin the Beguine,” and “Night and Day.” However, Porter’s only ballet is less well known, written as the result of a commission by the Ballets suédois and Darius Milhaud. It was Milhaud who recommended Porter to the company when they were looking for an American composer, describing him as “this elegant young American, who always wore a white carnation in the buttonhole of his immaculate dinner jacket and used to sing—in his grave, husky voice—songs he had written himself and which possessed the exact qualities that de Maré [Suédois Ballet patron] was looking for.” The result was “Within the Quota,” A critique of the 1921 Emergency Immigration Act, “Within the Quota” satirized American life and the mythology of instant success. While the ballet was lost for several decades, the recent rediscovery of the work and recent political events have created a small surge of renewed interest.

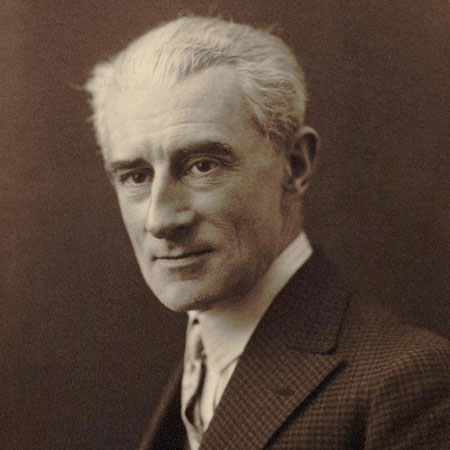

Maurice Ravel

(1875-1937)

Boléro

As did most of his orchestral works, Maurice Ravel’s Boléro began life as a piano piece—or at least, in this case, it almost did. In the late 1920s, the dancer Ida Rubinstein asked Ravel to orchestrate six pieces from Iberia, a set of piano pieces by Albéniz. In fulfilling the commission, Ravel ran into one of the realities of the 20th century—copyright law. As Spanish conductor Enrique Arbós had already orchestrated the dances, Ravel was prohibited from making the arrangement. Arbós was happy to waive his rights, but Ravel decided to switch directions, ultimately crafting a new work based on the musical form and Spanish dance known as the boléro. According to one story, Ravel played the work’s memorable melody on the piano for his friend Gustave Samezeuilh, asking, “Don’t you think this theme has an insistent quality? I’m going to try and repeat it a number of times without any development, gradually increasing the orchestra as best I can.” One of Ravel’s most famous compositions, Boléro, was the result.